REVISITING PLATO'S ACCOUNT THROUGH HISTORICAL, GEORGRAPHICAL, AND ARCHEOLOGICAL EVIDENCE

Atlantis Reexamined: A Sardinian Hypothesis

By Robert Ishoy

In any study of Atlantis, the primary source of analysis should begin with the only ancient records available on the subject: the two dialogues written by Plato, Timaeus and Critias. In these works, Plato provides a detailed description of the island of Atlantis, including its geography, structural features, cultural aspects, and industry. If Atlantis did in fact exist, then the details provided by Plato must serve as the benchmark for comparison. However, it must be noted that Plato wrote about Atlantis approximately 1,000 years after it supposedly ceased to be a significant civilization. This delay could mean that even Plato may have misunderstood the accounts passed down to him.

My hypothesis is that Atlantis was a powerful state based on the island of Sardinia in the Western Mediterranean Sea. This civilization reached its height during the pre-Bronze Age and early Bronze Age, roughly between 2000 BC and 1400 BC. These dates align with adjustments to Plato's timeline proposed by A. G. Galanopoulos¹. It is my belief that Atlantis controlled much of the rim of the Western Mediterranean and even attempted to conquer the advanced societies of the Eastern Mediterranean, including Minoan Crete, early Hellenic Greece, and Egypt. This would suggest that Atlantis was primarily a naval power—perhaps the earliest great sea power in history.

According to Plato, Atlantis was ultimately defeated during its invasion of the East by a combination of the Athenian navy and a series of cataclysmic earthquakes and floods². Together, these forces led to the downfall of Atlantis as a dominant power. Its defeat resulted in a significant setback for cultural development in the Western Mediterranean. However, with new research, the history of this region may prove to be far richer than previously believed.

Let us begin by addressing the confusion surrounding the location of Atlantis. Plato describes it as an island situated in the Atlantic Ocean beyond the Pillars of Hercules. He claims the island was larger than Libya and Asia combined and that a chain of islands extended from Atlantis westward toward a great continent that surrounded it³. The main difficulty in locating Atlantis lies in understanding the geographical perspective differences between Plato’s Classical Greece (circa 450 BC) and the earlier Hellenistic Greece (circa 1500 BC). By Classical times, most of the Mediterranean was well known to the Greeks, and the Atlantic Ocean was considered to begin beyond the Straits of Gibraltar—the "Pillars of Hercules." This worldview is still accepted today, but perceptions of the known world varied greatly even in Classical Greece.

Herodotus, in The Histories, was aware of Sardinia and referred to it as the "biggest island in the world"⁴. Yet today, we know Sardinia is smaller than its southern neighbor, Sicily⁵. Even as late as 98 AD, Tacitus referred to the Atlantic Ocean as "the unknown sea"⁶. Therefore, 1,000 years before Plato's time, the early Hellenes may have had a very different understanding of their world.

If we assume that the Western Mediterranean was unknown to the Hellenistic Greeks, then Sardinia fits Plato's description of Atlantis surprisingly well. Consider repositioning the Pillars of Hercules from Gibraltar to the Straits of Messina, located between the southern tip of Italy and Sicily. Sardinia is a large island just beyond those straits. From Sardinia, the Balearic Islands form a westward chain, and if one includes Spain, France, Italy, and North Africa, Sardinia is indeed surrounded by a "great continent."

Mediterranean

Mediterranean

Now let us compare Plato’s specific details of Atlantis to the geography of Sardinia around 1500 BC.

Sardinia

Sardinia

Plato writes: “For the most part, it was lofty and precipitous, except for a level plain immediately around the capital city. This plain was oblong-shaped and faced southward. The plain, in turn, was surrounded by mountains”⁷. Sardinia is roughly 90% mountainous, with the Campidano Plain in the south, which is oblong and opens to the Gulf of Cagliari⁸.

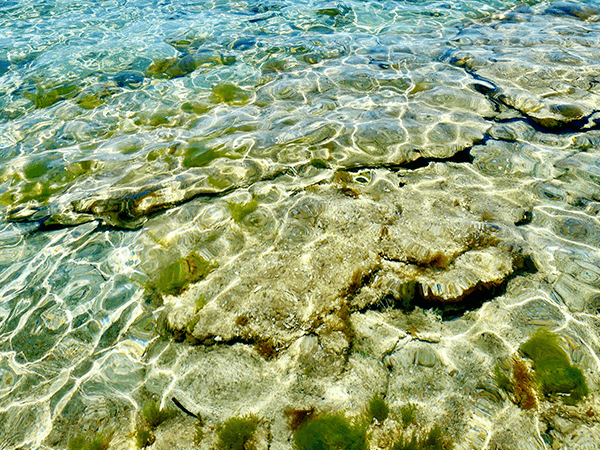

Plato also describes fountains of both cold and hot water around which the Atlanteans built warm winter baths⁹. Sardinia is dotted with hot and cold springs¹⁰, and archaeological evidence shows ancient “sacred wells” built near water sources¹¹.

He mentions an abundance of various types of wood¹². Sardinia was once heavily forested before deforestation by the Carthaginians¹³.

Plato notes that Atlantis teemed with tame and wild animals, including many elephants¹⁴. Ancient Sardinia was home to a variety of wildlife, including dwarf elephants¹⁵.

Mining was a key industry, and Plato describes a material called orichalcum, which was considered second only to gold in value¹⁶. This could correlate with obsidian, a precious resource in pre-Bronze Age Sardinia¹⁷.

Another element in Plato’s account is the bull cult of Atlantis, which involved worship of Poseidon and temples adorned with bull symbols¹⁸. In Sardinia, ancient rock-cut tombs in the northwest are decorated with bull heads in relief¹⁹.

Plato also references the use of three primary colors in Atlantean architecture: white, black, and red²⁰. These colors are naturally found in Sardinia and were used in Ozieri pottery²¹. Nuraghi buildings have also been discovered painted in red and black stripes²².

These examples show how remarkably Sardinia aligns with Plato’s description—perhaps more so than any other location in the world.

As further evidence, consider the Nuragic culture of ancient Sardinia. The Nuraghi built massive towers that resemble Mycenaean tholos (beehive) tombs²³. Radiocarbon dating places these structures as early as 1500 BC²⁴.

Interestingly, Egyptian records mention a people called the “Keftiu,” who came from the far West²⁵. These people were seen as a threat to Eastern Mediterranean civilizations. The name “Keftiu” is linguistically related to the Egyptian root for “pillar”²⁶—a reference that may correspond with the towering Nuraghi structures²⁷.

It is my hypothesis that the Nuragic culture, the Keftiu, and Plato’s Atlantis are one and the same. The archaeological remains on Sardinia may very well be the remnants of the lost civilization of Atlantis. The only unresolved aspect is the myth that Atlantis sank into the sea. For that, we must wait for future discoveries to confirm or challenge the legend²⁸.

Sardinia

Sardinia

Sardinia

Foot Notes and Bibliography to Thesis

Sardinia

Foot Notes and Bibliography to Thesis

-

Ramage, Edwin S. ed. Atlantis Fact or Fiction? Bloomington and London:Indiana University Press, 1978, p. 41.

-

Plato, Timaeus: The Dialogues of Plato, Translation by Benjamin Jowett;Great Books of the Western World. Chicago, London and Toronto: EncyclopediaBritannica, Inc. 1952, p. 446.

-

Plato, p. 446.

-

Herodotus, The Histories. New York: Penguin Books, 1954, pp. 109 and 389.

-

Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 24. New York: Americana Corporation, 1963. P. 299.

-

Ramage, p. 22.

-

Plato, Critias: The Dialogues of Plato, Translated by Benjamin Jowett; Great Books of the Western World. Chicago, London and Toronto: Encyclopedia Britannica, Inc. 1952, pp. 483 and 484.

-

Encyclopedia Americana. P. 299.

-

Plato, p. 483.

-

Guido, Margaret. Ancient Peoples and Places Sardinia. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1964. P. 28.

-

Balmuth, Miriam S. The Nuraghi Towers of Sardinia. Archaeology Vol. 34 Mr/Ap. 81. P. 42.

-

Plato, p. 484.

-

Guido, p. 29.

-

Plato, p. 482.

-

Guido, p. 29.

-

Plato, p. 482.

-

Guido, p. 44.

-

Plato, p. 484.

-

Guido, p. 49.

-

Plato, p. 483.

-

Guido, p. 42.

-

Guido, p. 57.

-

Balmuth, p. 40.

-

Guido, p. 111.

-

Ramage, p. 105.

-

Ramage, p. 67.

-

Balmuth, p. 43.

-

Ramage, p. 149.